Land-Use Planning is Bad for Cities

Throughout their history, cities have been comprised of many and varied uses, and quite often those uses found themselves self-segregated into districts, whether business, civic, residential or others. However this was rarely, if ever, an absolute condition. Shops and small businesses located in primarily residential neighborhoods, businesses in civic districts, and many other variations created degrees of use differentiation. There were adjacent uses of different types in various geographic areas of the city. And other than some designated governmental or civic districts (think Roman towns), these uses grew organically, in a generally unplanned manner, either in aggregated processes, or in the filling out of a planned area. Happenstance, market forces and physical characteristics of the city all played a part in how uses emerged and evolved in cities, but they were never a primary criteria for the pre-determined growth, layout or planning of a city.

That all changed in the second half of the nineteenth century and into the early twentieth, culminating with the 1926 Euclid v. Ambler decision. It was here that the planning profession, incorrectly, or at least unimaginatively, created the legal and ‘scientific’ foundation for the planning of cities based on projected use distribution; a distribution that was segregated by use to the greatest extent possible. It is important to remember, regardless of alternative interpretations, that the Euclid case and subsequent Supreme Court decisions were primarily about the constitutionality of limiting uses in residential neighborhoods. Sutherland is very clear in this issue:

‘We find no difficulty in sustaining restrictions of the kind thus far reviewed. The serious question in the case arises over the provisions of the ordinance excluding from residential districts apartment houses, business houses, retail stores and shops, and other like establishments. This question involves the validity of what is really the crux of the more recent zoning legislation, namely, the creation and maintenance of residential districts, from which business and trade of every sort, including hotels and apartment houses, are excluded.’

The logic here is based on the idea of exclusion, and an exclusion based on uses, not necessarily on exclusion of nuisance or danger (or at least perceived danger). And in many ways this makes sense as one contemplates the situation in most cities at the time of the decision. But Sutherland was also interested in the possibility of an overly narrow focus of this decision and points out in several instances that the court’s decision isn’t intended to limit the possibility, or inevitability, that many good uses, excluded in this decision, should be reviewed and either allowed to remain or allowed to be introduced.

Original Land Use Designations, Euclid

Of course this never happens, or at least doesn’t begin to emerge until the turn of the next century, fully seventy-five years after the original decision. Over those seventy-five years the idea of separation of land use has become entrenched in planning practices, and the idea of ‘land-use’, a concept that is aligned with zoning, becomes the single most important element of planning cities. It not only drives the various geographic areas of cities to stagnant, dead segregation, it also takes the central place of importance in projecting traffic, population growth, infrastructure needs, and essentially everything else that is ‘planned’ in cities.

In the end, this creates a city that is based on its least permanent aspect (uses, which can be changed in a matter of weeks), and compromises the most permanent, public rights-of-way, to the long-term detriment of the city. Cities are no longer planned by laying out future public rights-of-way. And in this new, scientific planning process, office uses produce different outcomes than single-family residential, multi-family residential or industrial, institutional, and all the other use categories that have evolved over the past century. Super blocks emerged to accommodate ‘vehicular movements’ within the blocks themselves, to the extent that block size in many subdivision ordinances was predicated on these ‘movements’, for example, instead of the physical outcome. There are myriad examples of this, and if it is ever in doubt as to the effect this had on our cities, simply look at the difference between cities laid out before and after the decision.

Euclid Land-Use/Zoning Plan

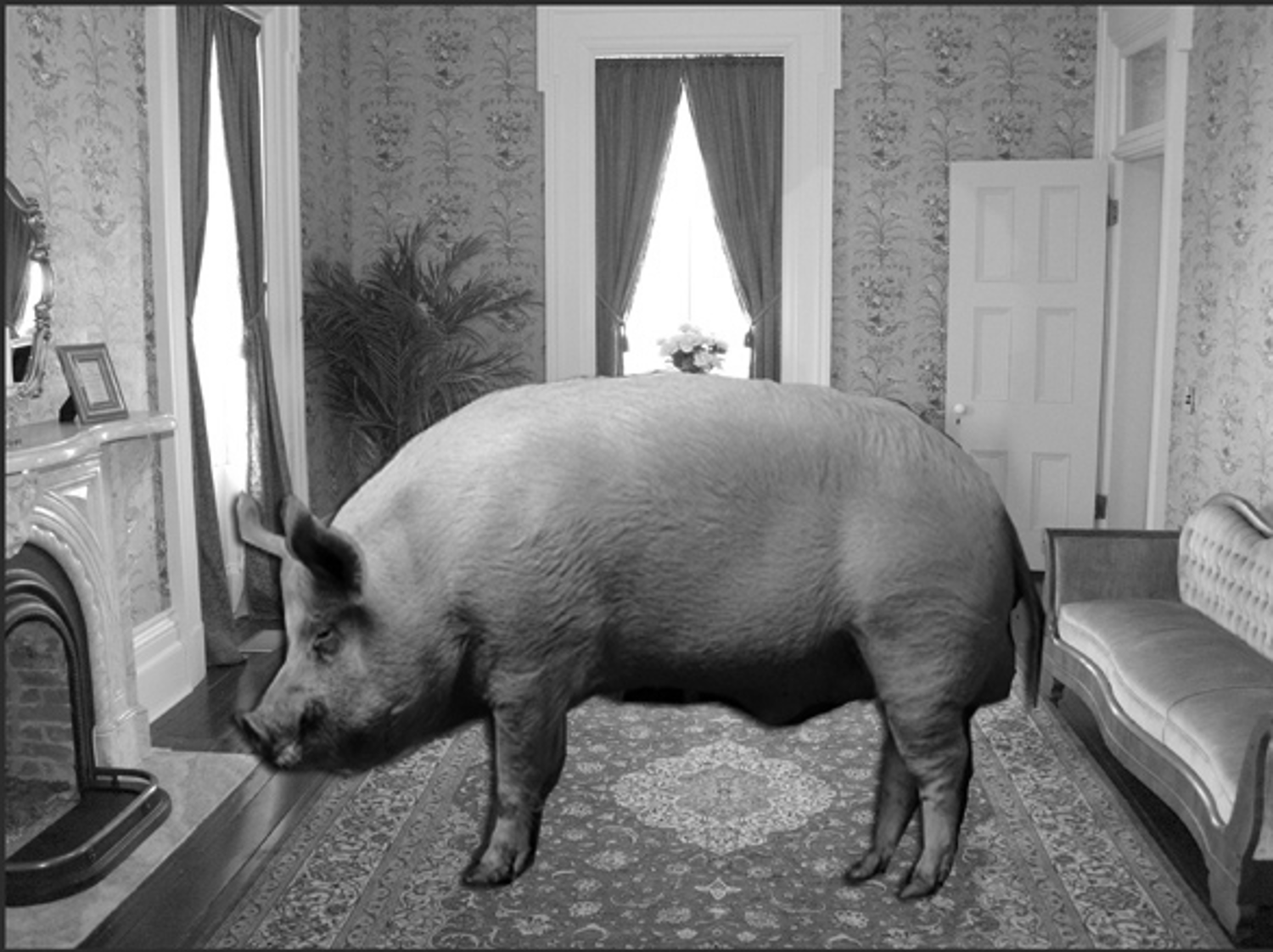

In the end the question is very simple. As we design and plan cities, whether repositioning areas of existing cities or creating them anew, why do we have land-use designations at all? What do these designations offer of value, other than a way to manage the city? There is absolutely nothing positive that comes from these designations in the planning process, but there are many negative impacts on cities that are a direct result of land-use based planning. To this end we are seeing a number of zoning categories emerging as mixed-use districts, which is really to say, no land-use designation. They generally have prohibited uses (Sutherland’s pig in the parlor), but the main goal of the districts is to have a mix of uses, which is in direct opposition to the idea of land-use designation.

The right thing in the wrong place, like a Pig in the Parlor

But land-use is so ingrained in our planning structure that it will be generations before we can finally remove this aberration from the process of planning cities. It offers planners, who otherwise would have no idea how a city should be formed, a kind of objective framework within which to make projections about the future characteristics and operations of a city. But in fact, it is probably the least objective set of criteria available in the planning process. For example, if parking is driven by land-use, then a central city office and a suburban office would have the same parking requirements, but clearly they don’t, or at least shouldn’t. The notion that something like parking, a thing for which we plan, is based on what people are doing inside the building is insane. There is absolutely nothing universal about how people get to office buildings. If this is the case, and it most certainly is, then what role does land-use have in the planning of cities?