Two-Sentence Subdivision Ordinance

In 1926 the United States created a legal precedent for zoning our cities, through the decision in the Euclid v. Ambler case. This was further reinforced with the publication of the final Standard State Zoning Enabling Act, which actually preceded the decision in the Euclid case. Zoning, and by extension land-use, became the primary way we think about planning cities. This is still with us today. The most important result of this is a situation in which we plan cities primarily by projecting future uses across specific geographic areas, even if those uses are mixed-uses.

But in 1928 the Department of Commerce published another Act, the Standard City Planning Enabling Act. In this simple and clear publication the DoC makes the case that any city should be laid out, first and foremost, through the projection of streets. It is essentially an act which enables cities to determine what is public (streets and parks) and what is private (blocks and parcels), and that these things are carved out of a plot of land, regardless of its ownership, status, and size.

The Enabling Acts

In the 100 years since, the first publication (State Zoning Enabling Act) has had far more impact on the physical landscape of the United States, and as a result much of the rest of the world. The basis of the subdivision of land has been rendered subordinate to the idea of planning around the future use of a place or a thing.

One significant aspect of this shift in thinking has been the idea that uses (building types, building uses, activities, people, etc.) should be separated. This has led to the emergence of single-use neighborhoods that have proliferated across the country and the world, and this has further led to a series of negative outcomes – unadaptable, homogenous, unsustainable, unhealthy, and inequitable development patterns.

One seemingly small outcome from this shift is exemplified by a single sentence that is embedded in almost every subdivision ordinance in every jurisdiction throughout the US; ‘Local streets shall be so laid out that their use by through traffic will be discouraged.’ This specific language is taken from the City of Atlanta’s 1957 Subdivision Ordinance, but similar language could, and still can, be found in ordinances everywhere. Embedded in this simple sentence is the idea that we shouldn’t be designing communities that are connected, and more specifically connected by streets.

Local streets shall be so laid out that their use by through traffic will be discouraged.

The diagram below shows us what the outcome of this simple, seemingly innocuous, sentence that is almost still universally supported in planning bureaus and neighborhoods alike.

No Through Streets

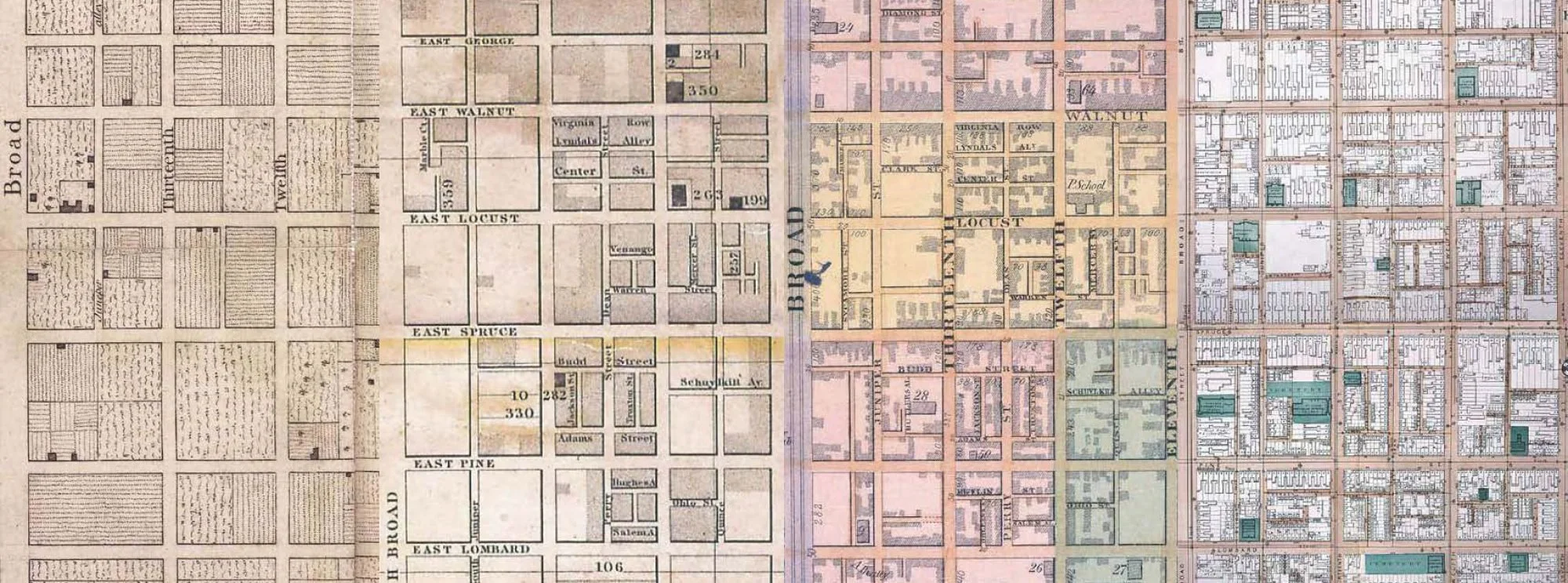

However, if we follow this standard, it means we will never end up with anything like the great cities that were laid out and built prior to this transformation. If we think about a city like Philadelphia (see image below), the first act was the laying out of streets, even though, as the first image clearly indicates, this was initially used as way to subdivide land for agriculture, even though the ultimate goal was to create a city. This series of plans of the city clearly shows how a system of streets can provide a simple way for cities to grow, and also, thankfully, a city where people can walk. In 1957, in Atlanta, not too many people were thinking about walking.

Adaptability Across Centuries

We now have subdivision ordinances that are incredibly complex, tied to comprehensive plans that are silent on the physical layout of cities, legally and conceptually incapable of projecting future streets. This drives cities to plan areas that are unwalkable, disconnected, and completely unlike the original city of Philadelphia and the thousands of other cities, towns, villages that preceded the these fundamental changes in the twentieth century. In fact, most subdivision regulations make it illegal to replicate Philadelphia, Manhattan, Savannah, Chicago or any other great city plan.

But there is a very simple solution. It is hard to imagine, but a simple, two-sentence subdivision ordinance would actually result in much better places, much better cities.

“A block is an area of privately owned land that is surrounded on all sides by public rights-of-way. No block perimeter shall exceed 1200 (pick your dimension) feet.”

That’s it.

What would the result of this be? Every new development or expansion of a city, or even a new city, would be connected and walkable. It might not be Savannah, ingenuous and beautiful, but it will never, by law, be the sprawling suburbs of the vast majority of 20th century (and unfortunately 21st century) America. In two simple sentences we would have a system that is incredibly clear, simple to understand, administer, and build.

This won’t guarantee great cities but it will preclude horrible cities. With this ordinance you could build Philadelphia, and in fact, the ordinance would incentivize something akin to Philadelphia, or other similarly planned cities, or as the City Planning Enabling Act so clearly outlines. The question we should be asking ourselves is why wouldn’t we do this.

Of course there are numerous reasons given why we can’t do this, but every one of those reasons, without exception, results in less possibility for great cities; less walkability, connectivity, adaptability, resilience, equity, etc.

One caveat, the dimension of 1200 feet is not sacred. In this case it represents a block that is, generally, 240 feet x 360 feet, which works pretty well for both buildings and people walking. Each jurisdiction could, should, and would change this to suit their needs (think Portland – 800 feet or Manhattan – 2000 feet, max, etc). The dimension should be the smallest number that accommodates the most varied set of building types.

Remember the Empire State Building, the largest building in the world for much of the twentieth century, sits on a block that has a perimeter of about 2000 feet, and it only takes up half the block! It’s footprint perimeter is about 1200 feet.