Airport Cities

There is a new phenomenon called the Airport City, or Aerotropolis. The idea behind these new developments is that there is a kind of ‘city’ that is developed around an airport, with particular uses and operations that both support the airport but also create an environment that might be more than a conventional logistics and business park. Generally these tend to be slightly modified versions of earlier landside developments. They are disconnected, fairly inflexible, and homogenous in terms of use. But if we are truly building a city next to the airport, it should work as a city first, and then as a development that is ‘landside’.

Airports are, almost without exception, autonomous transport hubs, not unlike highway interchanges. They are often framed as gateways to a city or region, but in reality they are simply a station in the temporal-based process of moving from one point to another in a completely disengaged experience. When one travels by air there is a sequence of disconnected events that are universal. You leave your home, drive or take a train to the airport, enter a very complex process-driven environment, which includes everything from check-in at the departure airport to processing at customs and baggage claim at the final destination. Then it is back to a car, train or taxi to your hotel. If you are lucky enough to be staying in a functioning city such as London or Chicago, you can, after you have checked in and unpacked, walk back out into the city and stroll about, visit a café or museum, or do anything that one does in a city.

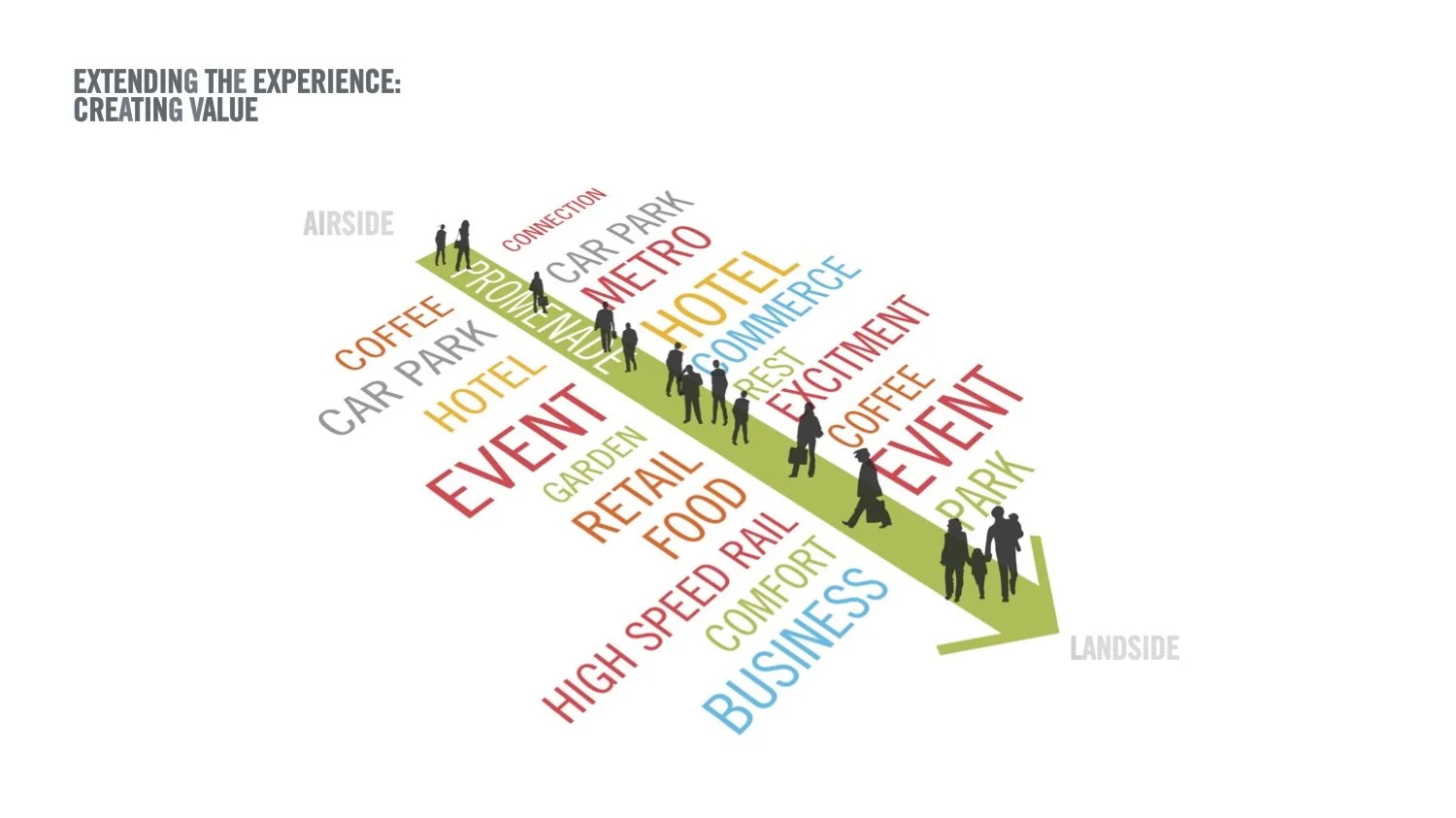

In this scenario everything one does from leaving the house to arriving at the hotel is very un-city. But if airport cities are to really be cities, either new or extensions of existing cities, then the airports themselves should be thought of as and should work like 19th century train stations or sea ports at city waterfronts. And the cities that surround them should be designed to take advantage of the airport as an integral and integrated part of the urban fabric.

When one arrives on the Eurostar from London to Paris, the connection from the Gare du Nord to the city is immediate. There is a front door to the station and when you pass through it you are immediately in the city. Or when arriving at the ferry terminal at Kadikoy, in Istanbul, you leave the ferry and you are immediately in the city, strolling through the beautiful pedestrian network sampling local foods and tasty baklava.

In contrast, arriving at Charles de Gaulle Airport or Ataturk Airport is a completely disorienting, dissociative experience. There is no connection from the airport to the ‘city’. One’s first thought upon arrival is coming to terms with the frustrating trip ahead to get from the airport to the city. Imagine instead walking out of the arrivals hall, bag in tow, and strolling directly to your hotel, check-in, and then wander through the city, with all its shops, businesses, cultural attractions and, importantly, people living there.

If this isn’t the end game, the goal of the Aerotropolis, then we aren’t really making an Airport City. We are just making another stop on the way through the dissociative journey that is air travel today. But there is no reason for this. While there are specific and sometimes onerous restrictions on development directly adjacent to airports, they are no more difficult to accommodate than regulations at city centers. There are use restrictions, height restrictions and of course issues of noise, but all of these can be dealt with through inventive and appropriate design. In fact, designing a new building in Knightsbridge, London is far more complex than meeting the requirements of a landside development alongside an airport, so this shouldn’t be an excuse for not making true cities out of the airport landside.

Everything today is called a city; airport city, science city, education city, retail city, etc., but in reality these should all just be cities, or parts of cities. Unfortunately, because they are generally single-use, disconnected developments they are cities in name only, and give real cities a bad name at that. But in the end, there is no reason for this. We should just be designing cities that happen to have airports in them.